High-speed steel (HSS) exhibits outstanding thermal hardness and wear resistance.

Its microstructure features abundant carbides distributed within a tempered martensitic matrix, endowing it with exceptional surface hardness, wear resistance, and fatigue crack resistance at both room and elevated temperatures.

It is widely used in cutting tools, rollers, bearings, and other wear-resistant components.

Traditional high-speed steel manufacturing processes, such as conventional casting (CC), electroslag remelting (ESR), and powder metallurgy (PM), present numerous challenges.

During conventional casting, significant segregation of carbon and alloying elements before crystallization results in slow solidification rates, leading to coarse network carbides.

This necessitates subsequent forging or rolling treatments, thereby reducing final yield rates.

Although the ESR process offers relatively faster cooling rates, it still produces substantial amounts of ledeburite structures and network carbides, resulting in poor engineering properties.

While powder metallurgy can produce high-speed steel with fine, uniformly distributed primary carbides and excellent mechanical properties, its complex heat treatment processes and stringent equipment requirements lead to high costs and low yield rates.

The advent of Advanced Manufacturing (AM) technologies has opened new avenues for high-speed steel production.

Techniques such as Powder Bed Fusion (PBF), Direct Energy Deposition (DED), and Material Jet (MJ) enable the fabrication of complex geometries, highly customized components, and parts with specialized properties—unconstrained by limitations of traditional manufacturing methods.

The growing application of these technologies in producing high-performance, high-speed steel products has significantly broadened the production pathways and alloy design possibilities for this material.

Development and Classification of High-Speed Steel

Since its invention in 1898, high-speed steel has evolved into multiple series, including the W series, Mo series, W-Mo series, vanadium- and cobalt-containing high-speed steels, and boron series high-speed steels.

Among these, M2 (W6Mo5Cr4V2) is the most widely used W-Mo series high-speed steel.

The mechanical properties of high-speed steel depend on its chemical composition and microstructure.

Used in demanding environments, it requires high wear resistance, hardness, and heat resistance.

Therefore, studying the effects of alloying elements on carbides to enhance its performance is crucial.

Carbide Types in High-Speed Steel

High-speed steel contains diverse carbide types, primarily including M2C, M6C, M7C8, and M23C6.

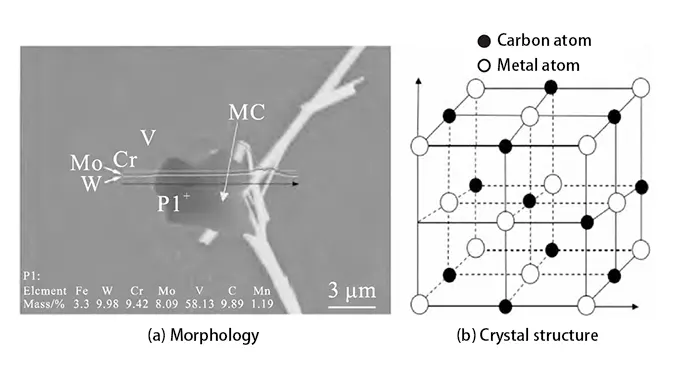

Among these, the morphology and structure of MC are shown in Figure 1.

It possesses a face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice structure and is a common carbide in high-tungsten high-speed steels, also frequently found in niobium-containing high-speed steels.

Its metallic element composition is diverse and can dissolve small amounts of other elements;

M2C exhibits a lamellar or fibrous morphology with a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) crystal structure.

It is prevalent in W-Mo series high-speed steels, composed primarily of Mo, W, V, Cr, and Fe. M6C is abundant in W and W-Mo series high-speed steels, presenting a fishbone-like appearance with a complex cubic lattice structure, mainly composed of Cr and Fe.

M7C3 exhibits a complex orthorhombic structure, commonly found in high-carbon, high-chromium steels, appearing as fishbone or strip-like structures;

M23C6 possesses a complex FCC structure and is one of the primary carbides in M42 high-speed steel, characterized by high Cr and Fe content and the ability to dissolve trace amounts of other elements.

Among different types of high-speed steel, the composition of carbides of the same type may vary, and differences in manufacturing conditions and techniques can also influence carbide morphology.

For instance, Ikawa et al. found that carbides in high-speed steel rolls produced by the spray deposition method exhibited a dispersed distribution with sizes below 10 μm, whereas carbides in conventionally cast rolls were larger and unevenly distributed.

The Effect of Alloying on Carbides in High-Speed Steel

1. Carbon (C)

C is one of the most critical elements in high-speed steel, typically ranging from 0.70% to 1.65%.

For high-speed steel used in casting rolls, the carbon content is 1.5% to 3.5%. Increased carbon content promotes carbide formation.

In low-carbon high-speed steels, carbides typically exhibit a network-like distribution, whereas in high-carbon grades, they predominantly form granular structures with more uniform distribution.

Carbon also enhances the volume fraction of carbides.

Excessive carbon promotes carbide agglomeration, disrupting uniform distribution and degrading tool steel performance.

Carbon content variations also influence carbide precipitation sequence and morphology.

For instance, in high-vanadium tool steels, increasing carbon significantly boosts carbide quantity while transforming morphology from rod-like and strip-like to blocky and spherical.

This alters the precipitation sequence and growth patterns of different carbide types.

2. Tungsten (W) and Molybdenum (Mo)

W and Mo exhibit strong carbide-forming capabilities in high-speed steel, forming carbides that alter its microstructure.

In most cases, 1% Mo can substitute for 2% W, producing identical carbides.

Their role in the alloy is commonly described using the tungsten equivalent [W] = W + 2Mo.

W primarily forms Fe₄W₂C and minor amounts of W₂C, partially dissolving into the matrix during quenching and precipitating as dispersed W₂C during tempering.

Mo mainly forms metastable M₂C eutectic carbides, which dissolve into finer M₆C and MC during subsequent hot working. Increasing W content promotes M6C formation while inhibiting MC precipitation.

However, excessively high W content leads to the formation of high-hardness, coarse-grained, skeletal MC during solidification.

Changes in Mo content affect carbides in high-speed steel rolls.

In Mo-alloyed and W-Mo-alloyed high-speed steels, increasing Mo content reduces total carbide volume and skeletal M6C, while MC carbides increase linearly.

3. Chromium (Cr)

Cr content in high-speed steel is approximately 4%. Its primary function is to enhance the material’s hardenability.

Working synergistically with other alloying elements, it elevates the recrystallization temperature and refines recrystallization grains, thereby strengthening the hardening effect of high-speed steel.

The carbides formed by Cr include M6C, M7C8, and M7C8. At lower quenching temperatures, M7C8 can dissolve completely, bringing the solid solution close to C-Cr saturation without affecting grain size.

These carbides largely dissolve into the matrix during quenching and heating, enhancing matrix stability.

Chromium also promotes the precipitation of secondary carbides MC and M2C, resulting in denser carbides during tempering.

However, excessively high chromium content can lead to the formation of unstable carbides during tempering, reducing the heat stability and red hardness of high-speed steel.

4. Vanadium (V)

V exhibits the strongest affinity for C, forming VC carbides characterized by high hardness, fine grain size, and stability.

These carbides precipitate first during solidification, typically dispersing throughout the matrix as particles or near-spherical grains.

This enhances the impact toughness, hardness, and wear resistance of high-speed steel.

Increasing V content helps refine the grain structure and promote network carbides in high-speed steel.

When V content is below 2%, its effect on microstructure is negligible.

Above 3%, significant grain refinement occurs, with increased carbide distribution forming a network or near-network pattern.

Further increasing V content coarsens the carbides; at 5% V, carbides become extremely coarse.

Additionally, V promotes the formation of M2C while suppressing M6C formation.

At high V and low C levels, quenched high-speed steel develops a “black structure,” leading to reduced hardness.

5. Cobalt (Co)

Co does not directly form carbides. Its primary function is to enhance the nucleation rate of MC and M2C during tempering while slowing their aggregation rate.

The Co content influences the morphology and size of carbides in as-cast high-speed steel.

Moderate addition refines MC, but beyond a certain threshold, MC size actually decreases.

Increasing Co content also causes rapid disappearance of curved, flake-like M2C carbides. Large-angle MC carbides decrease in size and adopt a coil-like morphology.

At approximately 0.82% Co, M2C size refines, whereas at 5.08% Co, MC carbides become ring-shaped with coarsened dimensions.

As Co content increased from 0 to 0.82%, the bending strength of the high-speed steel rose from 4,424 MPa to 5,251 MPa.

However, further increases in Co content resulted in diminishing gains in bending strength.

Co also reduces the size of secondary MC and M2C carbides during subsequent hot working and heat treatment, enhancing the hardness and red hardness of high-speed steel.

It promotes M2C carbide precipitation, increases overall hardness, and improves hot working properties.

6. Silicon (Si) and Aluminum (Al)

Although Si is not a carbide-forming element, it increases the quantity of tempered secondary carbides in high-speed steel and refines their size.

In W-Mo alloyed and Mo-alloyed high-speed steels, Si promotes the decomposition of M2C during heating, forming fine secondary carbide particles.

For example, silicon-added M2-0.8Si high-speed steel forging billets exhibit finer and more uniform carbides after quenching and tempering, with a bending strength reaching 4183 MPa and hardness up to 65.5 HRC.

However, excessively high silicon content leads to coarse carbides, adversely affecting mechanical properties.

Numerous researchers have investigated the application of aluminum in high-speed steels.

Pure Al added to M2 high-speed steel increases the area fraction of ferrite, accelerates columnar dendrite growth, and promotes the formation of M2C eutectic carbides.

Adding varying amounts of Al lowers the decomposition temperature of M2C eutectic carbides, causing them to decompose into MC and M6C after heating at 900°C for 3 hours.

This process alters the carbide morphology, reduces hardness, and disassembles the carbide network.

The Effect of Microalloying on Carbides in High-Speed Steel

Microalloying elements are typically added to steel at concentrations below 0.2%.

They interact with elements such as C, N, O, and S, forming secondary phase precipitates distributed within the matrix.

By adjusting process parameters, their solution treatment, precipitation behavior, and precipitate size can be controlled, thereby altering the steel’s properties.

Prior to research on microalloying in high-speed steel, microalloying elements had been extensively applied in cast iron.

Improving the distribution and morphology of carbides in high-speed steel through the addition of trace elements such as N, Mg, and rare earth elements has become a research focus.

Nitrogen (N): N shares many similar properties with C. When alloyed with other elements, it can form stable nitrides (such as VN) and interstitial solid solutions in certain complex carbides.

Appropriate amounts of N refine the eutectic network and primary carbides in cast high-speed steel, while transforming the morphology of M2C from lamellar to fibrous.

Fibrous M2C decomposes more readily into the more stable M6C and MC during forging and annealing.

For instance, Hara et al. introduced N by adding Cr₂N to molten alloys and observed that increasing N content primarily formed M₆ (C, N)-type carbonitrides while reducing the quantity of MC and M₂C eutectic carbides.

Halfa et al. observed that after adding N to AlSi41 high-speed steel, the carbides were primarily M6C and M7C3.

Due to the similarity in properties between N and C, N primarily replaces C in some carbides within high-speed steel, transforming them into carbonitrides and altering their crystal structures.

This significantly regulates carbides in high-speed steel, particularly effectively controlling MC-type carbides.

1. Boron (B)

Boron reacts with metallic elements to form large quantities of borides with high hardness and thermal stability.

A small amount of B dissolved in the matrix can partially replace C and other expensive alloying elements, improving the hardenability of the matrix.

In high-speed steels, B primarily segregates onto eutectic carbides at grain boundaries, promoting eutectic carbide segregation, increasing carbide numbers, and reducing eutectic carbide agglomeration during heating.

For example, Li et al. found that adding trace amounts of B to M2 high-speed steel increases the formation of lamellar M2C carbides, with carbides transforming from acicular to coarse lamellar structures as B content increases.

Yuan verified through first-principles calculations and experiments that boron-containing high-speed steel comprises pearlite, ferrite, retained austenite, minor martensite, and boron carbide.

The boron carbide phase predominantly distributes at grain boundaries, with hardness significantly increasing with boron content.

Astini et al. added 0.04% B to 6.5% V–5% W high-speed steel, observing a marked refinement in grain size and an increase in carbide volume fraction of approximately 1.2%.

The microhardness of the as-cast high-speed steel rose from 490 HV to 534 HV, with bending strength improving by over 10%.

2. Magnesium (Mg)

In cast iron, Mg promotes graphite growth in multiple directions, transforming flake graphite into spheroidal graphite.

It exerts a similar effect on carbides in high-speed steel.

Adding Mg reduces the size of primary carbides in high-speed steel, rounds their edges, breaks up large network carbides, promotes the transformation of carbides from MC to M2C, and simultaneously allows Mg inclusions to act as heterogeneous nucleation sites, enhancing carbide nucleation while limiting their growth.

For instance, Duan and Zhang et al. observed spheroidization of fishbone-shaped eutectic carbides at elevated temperatures after adding Mg to M2 high-speed steel.

Optimal refinement occurred at a Mg content of 0.008% by mass, with the effect on carbide size diminishing as Mg content increased further.

Unlike N and B, Mg influences carbide growth during solidification by altering the interfacial energy between carbides and other phases, thereby improving their morphology.

However, the specific mechanism remains to be elucidated.

3. Niobium (Nb)

Nb forms fine blocky NbC phases in high-speed steel, improving the morphology, size, and distribution of carbides precipitating in the ingot.

As Nb content increases, the degradation rate of M2C into MC and M6C accelerates, inhibiting eutectic carbide formation.

Simultaneously, NbC particles act as heterogeneous nucleation sites, reducing grain size and homogenizing the microstructure.

For example, in steel containing low niobium (0.0847%), lamellar and rod-shaped M2C alongside skeletal M6C are present.

However, when niobium content increases to 0.621%, only a single type of short, thin-layered rod-shaped carbide exists.

The effect of Nb on carbide formation is similar to that of V.

Due to Nb’s stronger affinity for C compared to other alloying elements, NbC precipitates early during solidification, inhibiting grain and carbide growth.

4. Titanium (Ti)

Ti exhibits high chemical reactivity, forming stable compounds such as TiC, TiN, and Ti(C,N) with C and N.

At elevated temperatures, Ti reacts with carbon in steel to produce substantial amounts of TiC, promoting heterogeneous nucleation and uniform dispersion of carbides.

Following heat treatment, these carbides exhibit spherical and granular distributions, enhancing the mechanical strength, wear resistance, and thermal fatigue properties of high-speed steel.

For instance, reports indicate that Ti-modified high-speed steel achieves impact toughness up to 10.3 J/cm², representing an increase exceeding 39%.

Dobrzański et al. observed chemical transformations in primary MC carbides after adding Ti to 11-0-2, 11-2-2, and 9-2-2 type W-Mo-V high-speed steels.

When Ti concentration in the steel is sufficiently high, VC transforms into a solid solution, producing a pronounced secondary hardening effect.

Advantages and Development of Advanced Manufacturing Technologies

Powder Bed Fusion (PBF) Technology

1. Selective Laser Melting (SLM)

As a highly flexible PBF technology, SLM demonstrates unique advantages in high-speed steel manufacturing.

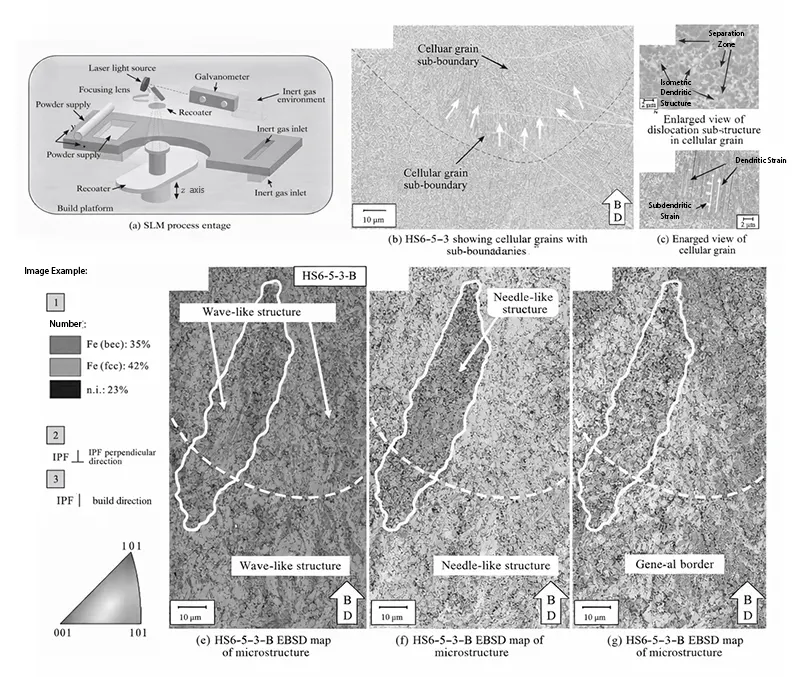

Its core principle, illustrated in Figure 2, involves using a high-energy laser beam to selectively melt powder particles in a powder bed according to a predetermined shape, thereby constructing components layer by layer.

Saewe et al. investigated the SLM manufacturability of HS6-5-3-8 and M50 high-speed steels.

By precisely controlling process parameters, they successfully produced crack-free high-speed steel components.

During SLM, critical parameters such as the temperature gradient in the melt pool and scanning speed profoundly influence grain growth orientation and microstructure.

Taking HS6-5-3-8 high-speed steel as an example, as the temperature gradient increases, the grain growth direction exhibits a tendency to shift from the melt pool edge toward the center.

Conversely, the central region of the melt pool, characterized by a relatively lower temperature gradient, often forms an equiaxed solidification structure.

This microstructural variation holds significant implications for the performance of high-speed steel, directly influencing key properties such as hardness, strength, and wear resistance.

2. Selective Laser Sintering (SLS)

SLS technology involves scanning a loose powder bed with a laser, partially melting the powder and sintering it into the desired shape.

Research indicates that M3:2 high-speed steel powders with different particle sizes exhibit significant differences in surface density and microstructure after SLS processing.

Among these, gas-atomized M2 high-speed steel powder treated via SLS forms a uniform and dense microstructure.

Dewidar et al. conducted SLS studies on Fe-1.39C-14.1Mo-3.6Cr high-speed steel powder, discovering that bronze infiltration treatment enables the fabrication of near-net-shape components with sufficient mechanical properties.

However, this research may exhibit certain biases in analyzing the types of carbides formed, providing further avenues for exploration and refinement in subsequent studies.

3. Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS)

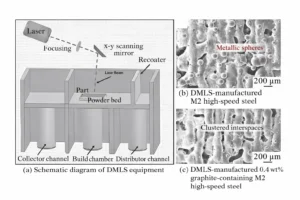

Figure 3 shows a schematic diagram of a DMLS device. Its fundamental principle involves scanning a focused laser beam across the surface of a loose powder bed to sinter the powder into complex components.

This process shares the same solidification mechanism as Selective Laser Melting (SLM), but DMLS is primarily applied to the fabrication of metal alloy components.

Although studies have demonstrated the feasibility of DMLS for manufacturing high-speed steel, the challenges involved should not be underestimated.

Chemical composition and sintering conditions play a critical role in the sinterability of high-speed steel during DMLS production.

Taking M2 high-speed steel as an example, limited research indicates that laser scanning speed and sintering atmosphere significantly influence its densification process.

Specifically, the sintering atmosphere directly influences porosity. Sintering in an argon environment yields lower porosity, thereby enhancing the quality and performance of high-speed steel components.

However, research on DMLS-manufactured high-speed steel components remains relatively scarce, necessitating further in-depth exploration.

4. Electron Beam Melting (EBM)

EBM technology utilizes a high-power electron beam in a vacuum to melt metal powder, thereby fabricating components with complex geometries.

Currently, research on EBM manufacturing of high-speed steel remains relatively scarce.

Ivanov et al. conducted EBM studies on HSS S6-5-2, finding that as beam power density increased, the size and quantity of M6C carbides gradually decreased. Simultaneously, martensite began to form, and the residual austenite content correspondingly increased. Jin et al.’s EBM processing study on S390 high-speed steel demonstrated that varying scan speeds resulted in distinct microstructural characteristics, including columnar and near-isotropic grain morphologies, as well as the distribution of discontinuous ultrafine primary carbides and retained austenite within the martensite.

These research findings provide crucial reference points for deepening the understanding of EBM technology applications in high-speed steel manufacturing.

Direct Energy Deposition (DED) Technology

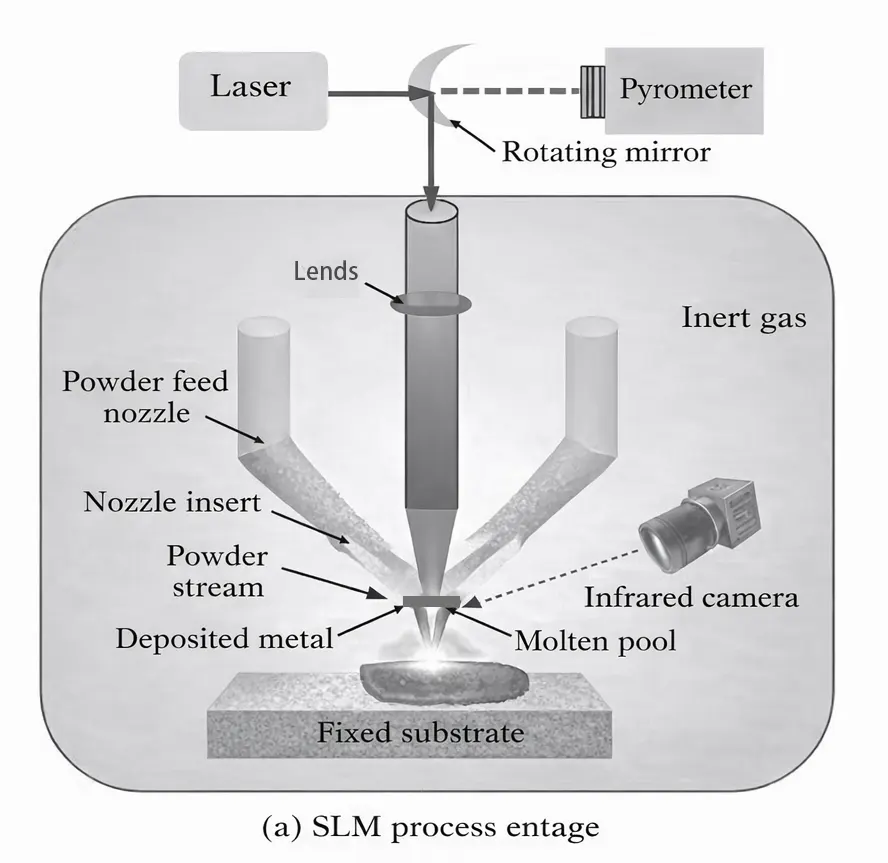

Figure 4 illustrates a schematic of the Direct Energy Deposition (DED) process.

In this process, the laser-based DED technique utilizes a powerful laser beam to deliver thermal energy, simultaneously melting metal powder injected through one or more nozzles and a specific substrate to form a dynamic molten pool. Subsequently, enhanced performance layers are deposited and solidified during component construction, building the part layer by layer.

This technology offers significant advantages, including the ability to manufacture large components, high deposition rates, and a broad process variable window.

Furthermore, DED technology can be employed to fabricate functionally graded/composite components, offering additional possibilities for optimizing the properties of high-speed steel parts.

In their study on DED manufacturing of two high-carbon high-speed steels, Rahman et al. discovered that during deposition and solidification, the molten pool could be effectively protected from excessive oxidation during manufacturing by strategically utilizing additional shielding gas nozzles and powder injection nozzles.

The resulting microstructure comprised martensite, retained austenite, and a carbide network, with carbides distributed in both grain boundaries and the matrix.

Crucially, process parameters critically influence component formability.

Therefore, precise control of these parameters is essential in practical applications to ensure the quality and performance of the manufactured components meet specified requirements.

Material Jet (MJ) Technology

1. Spray Forming (SF)

The SF process involves melting metal alloys in an induction furnace and atomizing them into fine droplets using high-pressure inert gas.

These droplets undergo heat exchange with previously deposited layers during flight, rapidly solidify, and deposit to form a billet.

SF offers several advantages, including high cooling rates, relatively simple manufacturing procedures, lower costs, and near-net-shape forming capability.

The microstructure of high-speed steel produced via SF exhibits fine equiaxed grains, delivering superior toughness and hot workability compared to traditional ESR and PM processes.

Research by Pi et al. on W18Cr4V high-speed steel fully substantiates this.

Their study revealed significant differences in velocity, temperature, and solidification behavior among droplets of varying sizes during flight.

Smaller-diameter droplets cool faster, reach the deposition surface at lower temperatures, and their motion and cooling behavior can be effectively predicted through established models.

This provides robust theoretical support for precise control of the SF process.

2. Co-Spray Forming (Co-SF)

Co-SF technology employs dual atomizers to simultaneously spray different high-speed steel melts, aiming to enhance production efficiency and optimize mechanical properties.

For instance, combining M3∶2 and M2 high-speed steels with carefully adjusted process parameters enables the formation of a gradient structure in the deposited layer, significantly improving bonding strength.

Experiments demonstrate that setting the austenitizing temperature to 1180°C achieves a hardness of 66 HRC, fully showcasing the immense potential of Co-SF technology in enhancing high-speed steel performance.

Impact of Composite Treatment Technology on High-Speed Steel Properties

Composite treatment refers to a surface treatment technology where tools undergo plasma nitriding followed by coating deposition.

Plasma nitriding forms a nitride layer on the tool surface, altering its microstructure, enhancing surface hardness, and creating a diffusion layer that provides an excellent bonding foundation for subsequent coatings.

Subsequent coating deposition, such as Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) and Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD), further enhances the tool surface’s hardness, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance.

As an emerging surface modification technique, this technology offers new avenues for improving the performance of high-speed steel tools.

This section aims to provide a comprehensive review of composite treatment applications in high-speed steel tools and their effects on thermal conductivity and surface roughness, exploring their potential and challenges in enhancing tool performance.

Application and Effects of Composite Treatment Technology in High-Speed Steel

Composite treatment technology enhances the wear resistance of high-speed steel.

Research by Tutar et al. indicates that AlSi H13 tool steel undergoes significant hardness improvement after composite treatment with AlTiN and CrN coatings.

Specifically, the hardness after AlTiN coating reaches 15 times that of H13 steel, while the hardness after CrN coating is 11 times that of H13 steel.

In abrasive wear tests, mass loss decreased by 2.7 times for CrN composite-coated samples and by 2.4 times for AlTiN composite-coated samples, fully demonstrating the significant effectiveness of composite treatment in enhancing tool wear resistance.

> High-Temperature Wear Performance of Composite Coatings

Ebrahimzadeh and Ashrafizadeh conducted TiN-TiAlN and TiN-TiAlN -CrAlN composite coatings on AlSi H13 steel.

They observed significantly improved wear resistance in treated samples during pin-on-disc wear tests at 250°C and 750°C, with TiN-TiAlN coatings demonstrating optimal performance characterized by minimal wear and reduced surface roughness.

Application of the TiN-TiAlN composite coating to forging dies extended tool life by 200%, further validating the effectiveness of composite treatment in practical applications.

> Improvement of Coating Adhesion by Composite Treatment

Additionally, the composite treatment enhances coating adhesion. Tillmann et al. investigated the effects of nitriding parameters on the adhesion of TiAlN and CrAlN coatings on AlSi H11 tool steel substrates.

They found that increasing nitriding time and nitrogen flow rate elevated surface hardness and nitrided layer depth, increased the critical load Lc3, and reduced scratch width.

This indicates that composite treatment significantly enhances adhesion between the coating and substrate, thereby improving coating stability.

Deng et al. investigated the effect of the N₂/H₂ flow ratio during the nitriding stage on the adhesion of AlTiN coatings on AlSi-H13 steel.

Results showed that samples with a hydrogen-rich ratio exhibited the best adhesion.

All composite coatings were rated HF1 in the Rockwell C indentation adhesion test, while the adhesion of the single-layer AITiN coating ranged from HF3 to HF4.

This further demonstrates the critical role of composite processing in enhancing coating adhesion.

> Optimization of Tool Performance in Industrial Applications

Composite processing technology also optimizes tool performance. Hawryluk et al. investigated composite treatments (particularly Cr/CrN layers) for hot forging dies.

They found that Cr/CrN coatings exhibited high wear resistance at room temperature, while Cr/CrN/AlCrTiN coatings delivered optimal performance at 500°C.

Although wear test results at elevated temperatures might favor the Cr/CrN/AlCrTiN coating, considering other factors such as critical loads Lc1 and Lc2 in sliding indentation tests, coating plasticity, and uniformity, the Cr/CrN coating proves more suitable for hot forging dies, effectively extending die life.

Paschke et al. applied a Ti-B-N multilayer coating composite treatment to DIN 1.2343 tool steel.

They found that the treated tools exhibited reduced geometric deviations and effective wear protection during forging, demonstrating significant advantages over untreated and nitrided-only tools.

This indicates that composite treatment can optimize the comprehensive performance of tools.

Effect of Thermal Conductivity on High-Speed Steel Performance

During the use of high-speed steel tools, particularly when machining low-thermal-conductivity materials such as titanium and nickel-based high-temperature alloys, the thermal conductivity difference between the tool and workpiece significantly impacts tool wear.

Due to the low thermal conductivity of these alloys, heat generated during machining is difficult to dissipate effectively, leading to elevated tool temperatures and accelerated wear.

In coated tools, elevated temperatures may cause substrate softening, making the coating susceptible to delamination and further increasing the risk of tool failure.

> Temperature-Dependent Thermal Conductivity of Hard Coatings

Martan and Benes investigated the thermal conductivity of TiN, TiAlCN, TiAlN, AlTiN, TiAlSiN, and CrAlSiN coatings from room temperature to 500°C.

They found that the thermal conductivity of all coatings increased with rising temperature.

Among these, the TiAlSiN coating exhibited the lowest thermal conductivity, with a relatively modest increase of approximately 46% when heated to 500°C.

The AlTiN coating demonstrated higher thermal conductivity but a lower growth rate of only 6%.

> Effect of Silicon Addition on Thermal Conductivity Reduction

The addition of Si elements enabled the formation of a nanocomposite structure in the coatings, significantly reducing thermal conductivity.

For instance, the thermal conductivity of AlTiSiN coatings decreased by 3 to 4 times compared to coatings without Si addition.

CrAl-SiN coatings exhibited low thermal conductivity across all temperatures, comparable to the performance of AlTiN/Cu multilayer coatings studied by Fox-Rabinovich et al.

> Thermal Insulation Mechanisms in Multilayer Coatings

Samani et al. demonstrated that TiN/TiAlN multilayer coatings exhibit lower thermal conductivity than single-layer TiN or TiAlN coatings.

As the number of double layers increases in multilayer coatings, the addition of Al to the TiN structure alters its columnar arrangement into thinner nanostructures.

This simultaneously enhances phonon scattering at interlayer interfaces and reduces phonon mean free path, effectively lowering the coating’s thermal conductivity.

For example, when the number of bilayers is 5, the coating thermal conductivity decreases from approximately 11.00 W/(m·K) to 4.92 W/(m·K).

When the number of bilayers increases to 100, the thermal conductivity further decreases to 3.25 W/(m·K).

Fox-Rabinovich et al. discovered that despite copper’s high thermal conductivity, incorporating Cu into AlTiN coatings to form multilayer systems actually reduces the coating’s thermal conductivity.

This occurs because the multilayer structure restricts phonon movement, thereby diminishing heat transfer.

Furthermore, the introduction of Cu enhances the coating’s lubricity and reduces the coefficient of friction.

These combined effects increase the tool life of coated cutting tools by 2.3 times.

> Anisotropy Effects in Multilayer Thermal Insulation Coatings

Bottger et al. investigated multilayer coatings combining TiN and AlCrN layers, discovering that their thermal insulation properties are closely related to anisotropy.

Theoretically, this combination can achieve anisotropy values up to 3.

However, actual measurements revealed lower anisotropy values than theoretical predictions due to deposition defects such as layer thickness variations and droplet growth.

Despite this, the 50 nm thick coating still exhibited high anisotropy, averaging close to the theoretical value, with anisotropy exceeding 2 under all test conditions.

This demonstrates the effectiveness of multilayer coatings in thermal distribution and highlights their potential for application in high-load cutting tools.

Influence of Surface Roughness on High-Speed Steel Performance

Surface roughness significantly impacts tool performance, particularly for coated tools.

Increased roughness negatively affects tool performance, while post-processing to reduce roughness improves coated tool performance.

In composite treatment applications, plasma nitriding increases surface roughness, thereby influencing the final roughness.

Abusuilik’s research indicates that the surface roughness of AlSi H13 steel affects its wear behavior.

Coatings with high roughness exhibit poor adhesion and increased wear. Nitrided samples demonstrate better performance due to the diffusion layer support.

Polishing and post-nitriding polishing enhance coating adhesion.

Do Nascimento Rosa et al. found that altering drill bit surface texture affects roughness.

Roughness increases after depositing TiAIN and TiAlCr-SiN coatings, while polishing reduces it.

Surface modification negatively impacts drill life, as high roughness hinders oxide layer growth and compromises coating wear resistance.

Saketi and Olsson demonstrated that increased coating roughness negatively impacts initial adhesion during sliding contact with 316L stainless steel, accelerating tool wear.

Post-deposition polishing reduces the coefficient of friction and minimizes material wear.

Wang’s research indicates that wet shot peening post-treatment improves the tribological properties of CVD coatings.

Reducing roughness enhances the wear resistance of coatings B and C, but the treatment negatively impacts coating A due to shot peening damage to the TiN layer.

Puneet’s research indicates surface roughness affects coating adhesion and HSS drill life.

Micro-shot peening reduces roughness and extends tool life. Combining drag finishing with micro-shot peening yields superior results by reducing edge stress concentration and improving coating uniformity.

Concurrent research indicates that roughness affects the application of AlTiSiN coatings on carbide tools.

Drag finishing reduces roughness and improves coating adhesion, whereas micro shot peening has the opposite effect, increasing coating spalling area and reducing wear resistance.

Conclusion

High-speed steel holds a vital position in modern industry, yet it also faces certain challenges.

Regarding limitations, traditional manufacturing processes such as conventional casting, electroslag remelting, and powder metallurgy suffer from low yield rates, poor engineering properties, and high costs, respectively.

While advanced manufacturing technologies present new opportunities, they still encounter difficulties in process control, efficiency improvements, defect management, industrial application limitations, inaccurate numerical modeling, lack of standards and specifications, and the arduous task of developing new alloys.

Although composite treatment technologies have shown effectiveness in enhancing high-speed steel performance, there remains room for improvement in process optimization, precise parameter control, and adaptability to different operating conditions.

Thermal conductivity and surface roughness significantly impact high-speed steel performance.

Current research requires deeper exploration into stabilizing surface roughness reduction processes and precisely regulating thermal conductivity.

Looking ahead, high-speed steel development will focus on overcoming existing limitations.

In manufacturing, advanced techniques promise more efficient and precise production through technological innovation and optimization, thereby enhancing product quality and productivity.

Composite treatment technologies will continue to evolve, further enhancing high-speed steel performance and expanding its applicability in more extreme operating conditions.

Regarding alloy design, greater emphasis will be placed on developing new high-speed steel alloys with superior performance and lower costs through precise control of alloying elements and microalloying element content and ratios.

Simultaneously, as demands for high-speed steel performance continue to rise, related research will become more in-depth and systematic, driving greater utilization of high-speed steel in high-end manufacturing and other fields.